|

| Buy F&SF • Read F&SF • Contact F&SF • Advertise In F&SF • Blog • Forum |

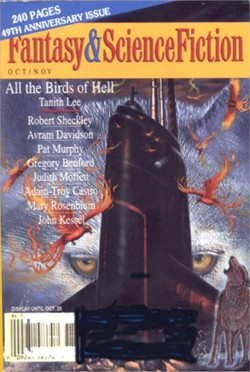

October/November 1998

|

Plumage from Pegasus

Imaginary Realist: The Life of Timothy Eugene, The Birth of Fabulaic Surmimesis. Written by Milton Sharp, uploaded by HarperOptics, 2025. Download price: E$35.00. Size: 2 meg (xvii + 458 pages, plus AV attachments). Download time: approximately two minutes through most ISP's. The story of sui generis author Timothy Eugene and of the strange cult of readers and writers his short life and three novels inspired still continues to fascinate. Although Eugene's work, subject of extensive criticism, has been continuously available since he first leapt into the world's literary consciousness, the author himself has been a figure shrouded in shadows and rumors. Not so any longer. Milton Sharp's superb biography of Eugene--based on five years of ground-breaking research and indefatigable interviews with the few people ever to meet the hermit-author - brings the "Psychopomp of Poultney" out from obscurity for all time. Also featuring Sharp's perceptive exegesis of Eugene's fictions, this volume seems destined to drive Eugene's literary cachet higher than ever. And although much of the factual mystery surrounding Eugene is hereby removed, the end result of this biography is paradoxically to foster a deepening of the aura of inscrutability attending this nonpareil and his novels. Sharp opens his story in 1985. In this year was born to Eudora and Sinclair Eugene a son they christened Timothy. The elder Eugenes were unlikely candidates to conceive and raise a literary genius. Subsisting on odd jobs and food stamps in Rutland, Vermont, they exhibited no affinity for literature or learning. In this respect, it was a cruel but necessary act of Fate which removed them from Timothy's life, in a car accident when he was only five years old and safely at home with a babysitter. Now the scene switches. Eugene's closest surviving relative was a widowed great-aunt, Frances Hooghly, resident of nearby Poultney, Vermont, and proprietor of a struggling turkey farm. She assumed custodianship of toddler Timothy, and full responsibility for his upbringing. Thus was Eugene's future course determined. The Hooghly turkey farm was a rural enclave that could have survived from a previous century or millennium. Miles from its nearest neighbor or commercial district, lacking a telephone or electricity, heated by wood and lit by kerosene, a battery-powered radio its only media connection, Eugene's new home - in fact, the only residence he would ever know during his life - was to be instrumental in shaping his peculiar perceptions and mind. Beset by endless grueling work simply to survive, Frances Hooghly - not unkind or unaffectionate, but supremely practical - quickly determined that little Timothy would have to assume his share of the chores. His education would consist of home-tutoring, as the overlong bus ride to and from the faraway school could not be accomodated. This prospect accorded well with Eugene's natural bent. The boy proved, from an early age, to be utterly agoraphobic, gripped by a neurosis that only worsened with age. During his teens for instance, on his worst days, even the usual trip from the security of his bedroom to the turkey sheds would prove impossible. Leashed to the farmhouse and immediate yards by his mental disability, Timothy Eugene lived an isolated life practically unimaginable to the wired and networked citizens of the late twentieth and early twenty-first century. Luckily for Timothy Eugene and for his future readers, the Hooghly homestead offered one major educational resource - and one further connection with the world. Years before Eugene's birth, in a barter transaction, Frances Hooghly had accepted a small library of old fiction consisting of moldering uniform editions of several Victorian novelists. Lining the farmhouse walls were the complete Dickens, the complete Trollope, the complete Thackery, the complete Balzac (in translation), and several others. These giants of realism were to be Eugene's tutors. He read and re-read them endlessly from approximately age ten until the end of his short life. They inspired him to believe that one career choice - other than turkey-raising - remained open to him: author. At age nineteen, in 2004 when his beloved great-aunt died of untreated pneumonia (contracted while trying to rescue a pair of prize turkeys from drowning), Eugene availed himself of his link to the outside world: a bent-armed antique Underwood typewriter, and the weekly arrival of the RFD postman. Sharp takes a small detour at this point in his study to survey other famous reclusive artists, illustrating what made Timothy Eugene unique. Giving precise thumbnail sketches of such figures as H. P. Lovecraft, Thomas Pynchon, Robert E. Howard, Marcel Proust, Henry Darger, and Joseph Cornell, Sharp illustrates one salient fact about all such creators: no matter how eccentric and sequestered they became in later life, all had fairly normal childhoods marked by extensive immersion in and acclimation to society. Such was not the case with Eugene. Seeing only a few tradesmen as they delivered necessities, never venturing from the farm property, Eugene was a modern "boy raised by wolves" (in this case, "raised by dead authors"). Sharp compares him to the perhaps apocryphal tradition found in some South American tribes: deliberate isolation of a child in a cave from birth, to foster an otherworldly connection that would turn the subject into a shaman. Timothy Eugene became a modern version of that shaman. Now bereft of kin, possessing a sharp and active mind, desirous of bettering his lot and expressing himself, young Eugene sat down at the typewriter and composed his first story. Like James Joyce's early, comparatively staid short fiction, it was only partially indicative of what was to come. "Hope Wears Feathers" (of course a volume of Emily Dickinson lay in the Hooghly cache) was a novella from the point of view of an aspiring and bright thirteen-year-old boy who resided on an isolated turkey farm with a single adult guardian. The farm's daily routines, the rich essence of such an archaic rural life, as well as the boy's dreams and ambitions, were rendered with heartbreaking vividness - as how could they not be? Upon completion, Timothy Eugene sent the piece out to Green Mountains Review in Rutland, where it was promptly snapped up. Against all odds, publication instantly brought Eugene many things: comparisons to Faulkner and Steinbeck, fan mail, and a number of solicitations from Manhattan publishers. If he could conceive of a novel, it seemed, he could easily sell it. But there was the rub. What was Eugene to write about? He had exhausted his stock of first-hand experience with the one novella. At the same time, his worship of the great Victorian realists dictated that he should embark upon a major project of large scope, a vast and intricate tale aiming to encompass truthfully all of modern society and range across all socioeconomic scales. Eugene knew of the modern world only what he could filter from the few radio programs and occasional fish-smelling newspapers that entered his house. For instance: he knew from observing their passage overhead that airplanes existed; but he had never seen one up close, nor any supporting infrastructure like airports. ""Computers" he had heard of, some sort of mechanical brains; but how a person interacted with one was blank to him. Cars he had seen also, but never a "gas station." Likewise, the most common customs and manners and recreations were utterly alien to him; what, for example, was "breakdancing" or "a basketball playoff" or "a press conference" or "a Chief Executive Officer"? And so on and so on, through the catalog of early twenty-first-century existence. Yet Eugene had held for a long time now - in his active imagination -nascent pictures of these myriad objects and activities. His confidence and enthusiasm led him to believe he had a firmer grasp of things than he actually did. And the more he contemplated life outside the Hooghly turkey farm, the more he convinced himself that he had some real conception of what it entailed. Here in his narrative, Sharp pauses for a bit of amateur psychoanalysis. Bravely, he tackles the essential question any reader of Timothy Eugene's three astonishing novels must ask: did Eugene really believe he was depicting reality, or was he simply constructing what he knew to be castles in the air, semistandard "fantasy" or "magical realist" novels? After weighing each view, Sharp descends firmly on the side of the first proposal. Maintaining that Eugene worshipped his Victorian role-models to such a degree that he could never betray them by "falsifying reality," Sharp insists that the young writer was scrupulous in depicting only what he honestly believed to be the "real world." A further proof is the internal consistency among the three books. Once having established a "fact," Eugene never retreated from or contradicted it. In a burst of creativity, Eugene quickly drafted a proposal for a novel. He accepted the first offer for it (from a perhaps overeager publisher, St. Merton's, who soon came to regret their haste), although he could have held out for more. Ordering a bottle of ink to replenish his obsolete ribbon, along with reams of paper, the Psychopomp of Poultney fell to writing. Thus was born fabulaic surmimesis: the unwavering depiction of a reality inhabited by only a single citizen. Anyone who has ever stumbled upon The Casserole of the Linebacker (2007) without forewarning of its unique nature can surely recall the heady sense of disorientation and cognitive estrangement the book engenders. Here is a tale that plainly fancies itself to be the apex of realism, yet which depicts a world as strange as, say, Peake's Gormenghast (1950) or Ishmael Reed's The Free-Lance Pallbearers (1967). Yet nowhere is there a lick of irony or deliberate straining for effect. The main thread concerns the story of Lyle Rosebower, restaurateur and professional athlete for the Chicago Cowslips, his wife, Becky, a Greyhound Bus Lines stewardess, and their quest for happiness in the face of the machinations of the villainous radio-talkshow host, Sternman Partch. Secondary characters number in the dozens, and the subplots are manifold, as with Dickens. Particularly engrossing is the plight of young Goodly Ament, a teenage cheerleader who falls under the sway of a travelling Satanist preacher and clove-cigarette smuggler, Lance Allson. On the simple level of story-telling, Eugene proved that he had a decent grasp of cause and effect, and of such common emotions as love, hate, and avarice, much like any other competent writer. But in the staging of action and in the details of "everyday" life provided, such an abundance of oddness exists as to render the novel utterly otherworldly. Even those aspects of reality which Eugene intuited almost correctly are off by a disturbing hair. Just the costumes of the characters - Lyle's ruffled collars and velvet jodphurs when hosting at his dining establishment and his spike-topped playing helmet; Becky's harem pants and Partch's swallowtail coat - are enough to conjure a scene out of, say, Jack Vance. Add to this elaborate word-pictures of the absurdly designed appliances and vehicles, buildings and possessions populating Eugene's world, and the final effect is one of opening a window onto a universe that is simultaneously ours and not ours. Yet it must be stressed that not one event incompatible with scientific fact or the tenets of realism is ever introduced. The reaction to Eugene's first book ranged from utter bewilderment and castigation to indifference to enthusiastic adoption by the avant-garde, who viewed Eugene with complete misunderstanding as a fellow literary transgressor. St. Merton's - who had almost asked for their advance back when they received the manuscript - quickly decided for bottom-line reasons to drop Eugene. Undaunted, he began his second book, casting about for a smaller press to print it. Explosion at the Fireworks Factory (2011) eventually found a home with Four Wallabys Eight Widows Press. This tale of a small town--seen through the eyes of the Pickwickian Wittold family, whose lives centered around the titular factory - earned Eugene his most famous critical quote, from The New York Times critic Mistakeo Kakophany: "Reads like a mix of the worst Robert Coover and the best Doctor Seuss." Eugene's growing bafflement and hurt at the incomprehension of readers and reviewers was evident in his third and final novel, Starmaker Machinery (2020), a bildungsroman about a novelist named Muchly Small. (The only music station available on Eugene's receiver was devoted to oldies, and Eugene was particularly fond of Joni Mitchell, another kindred soul.) Despite - or perhaps because of - this new wounding, Eugene produced what many have come to regard as his masterpiece. An aging yet perceptive John Crowley, just finishing up his own quartet begun with Ægypt (1987), lamented that his book had the misfortune to be released in the same year as Eugene's. The critical consensus, however, was much less kind. At age 35, Eugene paused to reconsider his whole esthetic goal and method. Fancying himself the reincarnation of George Eliot or Wilkie Collins, he instead found himself reviled as that most detestable thing, a "fantasist." Sharp speculates that he must have finally experienced a critical mass of doubts about his self-developed weltanschauung. And so he made his fatal mistake. He decided to broaden his intimacy with the world. Purchasing a computer, subscribing to a dozen online newspapers, bringing a surround-sound HDTV monitor and a satellite dish into his newly electrified hovel, Eugene made contact at last with the world around him. A Good Samaritan postman found Eugene shortly thereafter, empty of life in front of his new audiovideo digital connections. Cause of death was indeterminate. Like one of his feathered charges, Eugene had simply "drowned" in the flood of distasteful information so at odds with his own precious mental constructs. Sharp wistfully concludes: "We may only hope that the afterlife includes the whimsical unborn world Timothy Eugene believed in, and that even now he rides those famous caterpillar-jointed trolley cars to the crest of his lurid San Francisco, there to gaze upon Eskimotown and a Golden Gate Bridge that connects the city directly to Seattle, where all the coffee-shops feature miniature braziers on each table, and the women are all beautiful in their dirndls and wimples." This reviewer concurs with a heartfelt "Amen." | |

|

| ||

To contact us, send an email to Fantasy & Science Fiction.

Copyright © 1998–2020 Fantasy & Science Fiction All Rights Reserved Worldwide

If you find any errors, typos or anything else worth mentioning,

please send it to sitemaster@fandsf.com.