|

| Buy F&SF • Read F&SF • Contact F&SF • Advertise In F&SF • Blog • Forum |

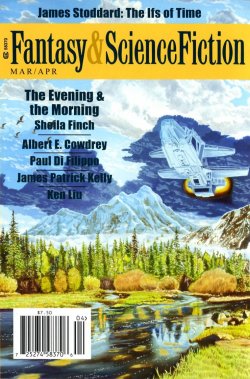

March/April 2011

|

Books Detour to Otherness, by Henry Kuttner & C. L. Moore, ed. Stephen Haffner, introduction by Robert Silverberg, afterword by Frederik Pohl, Haffner Press, 2010, $40. ANY OF US who teach or speak on a regular basis develop a set of shticks, modules that we assemble into various configurations depending on the occasion. We're like unimaginative banjo players, rolling off standard licks to fill available space. One of my banjo rolls has to do with rereading, with returning over the years to books that have been formative, and with the manner in which these books change. You settle down with To Kill a Mockingbird, which you first read upon publication, living in a Southern town much like Scout's and dating a girl whose Boo Radley-like uncle stood motionless facing into the corner for hours as the two of you watched TV, or you pick up a much-creased, smelly More Than Human, the book that more than any other made you want to write, and find yourself muttering, half in jest, half in fear, "Remember how we used to have so much fun together?" Recently I reread Alfred Bester's The Demolished Man, first encountered at age twelve, and while cringing at simplistic motives, unabashed lack of subtlety, pedal-to-the-metal hyperbole, and the datedness of it all (particularly with the Freudianism it's awash in), still I marveled at the manner in which Bester sucks you instantly into this society and this world, at the concept, the momentum, and many of the visuals—and at Bester's ambition. At the time, I was thinking again about an intuition I've had for years, that science fiction seems to need a periodic return to its origins to regather strength. I recalled how so many of my students who write fantasy and science fiction know little or nothing of the genre's history. And having just written about a Kornbluth biography for my last column here, I suppose I must have been glancing a bit more often at the rearview mirror. When my wife Karyn and I first met, I was struck by the manner in which she would read favorite books again and again. And not only favorite books, but whole series—even the greater part of the run of a writer's work. She's read some books a dozen or more times in the twenty years we've been together; she just flat uses these suckers up. We order new containers when the old ones fall apart. Chomp: in a weekend another soldier goes down. Chomp: the third volume of a trilogy. She'll sack out on the couch with tea and barely move till a book's done, consuming in a few hours what had taken writers not unlike myself months and years to create. Opus-Devourer, as I began to think of her. In the nicest way, of course. For her, and for all the influence a steady diet of fantasy and science fiction has had upon her life, some books are comfort food, meatloaf and mashed potatoes, bringing on a tacit sense of contentment and order. Books can lift us from "dailyness," they can rescue us momentarily from what Baudelaire called the quotidian frenzy. Books can confirm or challenge our opinions. Books can terrify us. They can do all these things at the same time. Now, into this slurry of reverie comes a dreadnaught collection of stories by Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore.

In Weird Tales's November 1933 issue appeared a story titled "Shambleau." Its opening sentences find Northwest Smith stepping into a doorway, hand on his heat-gun's grip, eyes narrowed. Strange sounds were common enough in the streets of earth's latest colony on Mars—a raw, red little town where anything might happen, and very often did. But Northwest Smith, whose name is known and respected in every dive and wild outpost on a dozen wild planets, was a cautious man, despite his reputation. The story's author was a twenty-two-year-old named Catherine Lucille Moore. Shortly the editor received a letter of praise from none other than H. P. Lovecraft. Another admirer, who would write "The Graveyard Rats" (1936) in homage to Lovecraft, was twenty-five-year-old Henry Kuttner. Initially, like most readers, Kuttner had no intimation that Moore was female. They were married in 1940, after which, for fifteen years or so of furious activity, most of their work was done in collaboration, so that even they could scarcely tell where one began, the other left off. The writing slowed markedly around 1953, and by 1958, when Kuttner died at age forty-three, he was well on his way to earning an MA from USC, reportedly with the intention of becoming a clinical psychologist. Those late stories, such as "Home Is the Hunter," "Two-Handed Engine," and "Rite of Passage" (the last included in the volume under discussion), were at the top of the couple's form. Kuttner also published three mystery novels in this period, though the last two may have been written by others. Moore went on to write for the media, first completing movie scripts that she and Kuttner had begun together, then providing episodes for TV shows like Maverick and 77 Sunset Strip. Eventually she remarried and stopped writing altogether, seeing one final collection, The Best of C. L. Moore (Del Rey/Ballantine 1975), before her death in 1987. Damon Knight expressed the general take on the collaboration: "Kuttner's previous stories had been superficial and clever, well constructed but without much content or conviction; Moore had written moody fantasies, meaningful but a little thin…together, they began to turn out stories in which the practical solidity of Kuttner's plots seemed to provide a vessel for Moore's poetic imagination." The bicameral Kuttner-Moore opus includes something on the order of a dozen fantasy and science fiction novels, seven mysteries, at least twenty collections during their lifetimes and since, and well over 200 short stories. It would be difficult to overstate the influence their work had on the field. Bob Silverberg notes in his introduction how closely younger writers like himself, Phil Dick, and Robert Sheckley studied those "lean, efficient stories" that Kuttner and Moore perfected, stories "beginning with a quick statement of a complex and often paradoxical plot situation, followed by a few paragraphs of exposition to resolve enough of the paradox to keep the reader from utter bewilderment, and culminating in a satisfying and often dark and disturbing plot resolution." Richard Matheson dedicated I Am Legend to Kuttner, as did Ray Bradbury his first collection, Dark Carnival.

Detour to Otherness brings together two classic Ballantine collections, Bypass to Otherness and Return to Otherness (1961 and 1962), plus eight additional stories, for a total of twenty-four stories and 568 pages. Many of what one might think of as standards are missing—"The Twonky," Moore's "No Woman Born" and "Vintage Season," "Mimsy Were the Borogoves"—but as such, these are readily available, and the range of work overall (remember those 200-plus stories) is well represented. The collection opens on a Hogben story, one from a series about mutant hillbillies who are (Really! They are!) just like the rest of us.

Farther along comes the first of the Gallegher stories, with the dipsomaniacal genius waking from a bender to find what he has wrought this time and do his best to figure out why the hell he wrought it, what its use might be. The robot stood proudly before the mirror and examined its innards. Its hull was transparent, and wheels were going around at a great rate inside.

A recurrent Kuttner-Moore theme, that of children become alien, children augmented by forces beyond our ken—home ground for "The Twonky" and "Mimsy Were the Borogoves"—finds voice here in "Absalom." Similarly, in "The Piper's Son," one of the five "Baldy" stories eventually collected by Kuttner as Mutant, not just children but all humanity is undergoing augmentation. Everywhere here we encounter fertile ideas, a natural, easy momentum, well-limned characters, authentic surround, unexpected turns, and an ever-masterful control of the anticipation and surprise that's at the heart of all narrative—doors slowly opening onto new and often inhospitable worlds. At the end of "Absalom" a father, one of a generation superannuated by its genius children, sits mired in his half-life. Absalom…was a good son. He called daily, though sometimes, when work was pressing, he had to make the call short. But Joel Locke could always work at his immense scrapbooks, filled with clippings and photographs about Absalom. He was writing Absalom's biography too. He walked otherwise through a shadow world, existing in flesh and blood, in realized happiness, only when Absalom's face appeared on the televisor screen. But he had not forgotten anything. He hated Absalom, and hated the horrible unspeakable bond that would forever chain him to his own flesh—the flesh that was not quite his own, but one step farther up the ladder of the new mutation. Sitting there in the twilight…Joel Locke nursed his hatred and a quiet, secret satisfaction that had come to him. Some day Absalom would have a son. Some day. Some day.

Reading and rereading these stories, one has to wonder (and especially one already peering into the rearview mirror) why it is that Kuttner and Moore are so nearly forgotten. Aside, naturally, from the fact that their books are not sitting in glossy uniform paperback editions on shelves at WalMart and Barnes & Noble. And aside from the general truth that, in the arts, innovators pass the torch on to popularizers. Few of us listen to Lonnie Johnson these days. Many listen to Stevie Ray Vaughan—even wear the hat. Certainly the work is dated. The earliest of these stories is from 1940, the most recent from 1956 and 1958; the bulk are from the early to mid-forties. Narrative conventions have changed, social norms have shifted and shifted again, and many of the elements that initially gave the work such impact, that made it so startlingly original—sharply depicted characterizations, the attention to detail in the writing, the moodiness of settings, its moral gravity, even the ideas—have long since passed into the mainstream of science fiction, and therefrom to film and TV. Time is a careless shepherd. Kuttner's and Moore's work is very much of a specific instant, suspended back there during science fiction's golden age and the last hurrah of the pulps with dozens of magazines needing material. It was a passage even then narrowing as newfangled paperback novels supplanted the role of magazine fiction. And though they wrote novels, Kuttner and Moore were primarily short-story writers. They were, too, extremely versatile, ever hopping from horse to horse, hard to get a hold on. Their contributions, the directions in which they urged the field, the facility and ambitions they fostered, are massive. And they are forgotten. Henry Kuttner and Catherine Moore had little if any expectation of their work enduring. And if they began (as many of us do) with thoughts of changing the world, those notions soon dissolved into the dailyness of filling pages, finding publishers, reaching always for the next elusive check. It was a hard life at the best of times. Recalling Kuttner's and Kornbluth's deaths in 1958, Kuttner at forty-four, Kornbluth at thirty-five, Bob Silverberg has noted: "I was only twenty-three then, but I somehow realized right away that these two men had literally died from writing science fiction and I was afraid that I was going to die too." For whatever reasons, Kuttner's and Moore's dual career seems to have been on a wind-down, or at least on pause, those final years of Kuttner's life. Two hundred stories, eighteen or twenty novels—that's a lot of words. The field was changing around them. And they were changing from within. You try sitting in a room twelve or sixteen hours a day putting words on paper. It can be like a protracted adolescence, you look up one day and it hits you: you're thirty, or forty, you haven't done much living, and what you wanted before just doesn't seem...enough. As writers, what we have to work with, our principal, is personal history—our thoughts, the way we put the world together, the way we've become who we are—and like any capital, without gains, eventually it is expended. At Kuttner's death, both he and Moore had returned to school. Did they feel a need simply to get out there, to recharge, to rebuild their principal? Would there have been further, still more ambitious, more startlingly original stories? One hopes. One always hopes. | |

|

| ||

To contact us, send an email to Fantasy & Science Fiction.

Copyright © 1998–2020 Fantasy & Science Fiction All Rights Reserved Worldwide

If you find any errors, typos or anything else worth mentioning,

please send it to sitemaster@fandsf.com.