|

| Buy F&SF • Read F&SF • Contact F&SF • Advertise In F&SF • Blog • Forum |

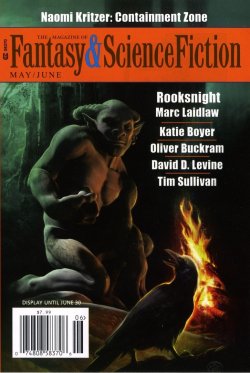

May/June 2014

|

Films IMITATIONS OF LIFE

We're talking about the world's most famous monster, right? Yes…but there's something more. These boilerplate descriptions of Mary Shelley's produced-and-abandoned artificial man also work remarkably well as snarky metaphors for Stuart Beattie's new film, I, Frankenstein. At least they did for venomous opening-day bloggers who seemed especially perturbed that Lionsgate had canceled the usual advance press screenings, leaving anyone with a deadline scrambling—and paying—for some late-night commercial showings on the eve of the opening. After enduring nearly a year of postponed release dates, feeling betrayed and resentful in the way only fanboys and fangirls can be, the villagers were up in arms, and out for blog. I attended a first screening at a major Los Angeles-area multiplex. Although the film was showing in three different formats—2-D, 3-D, and Imax 3-D—not a single display ad appeared in any local newspaper—a particularly ominous sign in the world's movie epicenter, along with the fact that I was the only patron in a largish stadium-style auditorium. While I, Frankenstein is not as bad as you may have heard, that doesn't mean it's particularly good, and it never achieves the saving grace and glow of high camp. It's almost slavishy derivative of the Underworld franchise (from the same producing company, Lakeshore Entertainment), and adapted from a 2009 graphic novel by Kevin Grevioux (also a member of the original Underworld story writing team). Where Underworld morphed into a series of video games, I, Frankenstein decided it was a video game from the get-go. Aaron Eckhart plays the creature, named Adam Frankenstein (justifying, for once, the often careless use of the surname for the monster). Eckhart's casting must have risen from his monstrously disfigured turn in The Dark Knight, though he's nowhere as repellant here. He's a well-trained actor who hits all the requisite notes and attitudes of brooding alienation, and looks great without a shirt, even with a torso crisscrossed with keloid scars. But I, Frankenstein is so cartoonish you can't always be sure you're looking at a real actor or a live performer motion-captured and jolted alive in a computer. And the actors aren't called upon to really speak dialogue. They intone. After the first few minutes, in which the Shelley novel is glibly recapped, then totally forgotten, the monster's story plays second fiddle to an ancient, ongoing war between heaven and hell, represented here by living gargoyles (the angels) inhabiting a massive gothic cathedral, and an uber-scary race of demons. We're told the opposing teams are fighting for the survival of the human race, which is pretty much AWOL in an unnamed European city that's as desolate and uninhabited as The Crow's Detroit. For two hundred years, the Demon Prince Naberius (Bill Nighy, the memorably high-flying vampire from Underworld) has been assembling an army of corpses he wants to possess demonically in order to conquer the world and/or destroy the human race, even if those motivations are more than a little contradictory. For some reason, demons can possess only soulless living (or reanimated) bodies (not the way things usually work in demonic possession films, but never mind). But Adam is presumably soulless, has the only copy of Victor Frankenstein's notebook on the secrets of reanimation, and therefore is the key (somehow) to hellishly infecting all those corpses in Naberius's bottomless subterranean storage facility that's straight out of another cartoony horror adventure—remember Dracula's vast hive of cloned bat-babies in Van Helsing? Yes, it's all very complicated and confusing, but just keep reminding yourself: there's not going to be a quiz. Eckhart, Nighy, Miranda Otto (as Leonore, the Gargoyle Queen), and Yvonne Strahovski (from Dexter) as Dr. Terra Wade (Naberius's supposedly brilliant, supposedly well-compensated, world-famous electrobiologist who nonetheless is forced to live in a burned-out shithole of an apartment) are all more than competent performers who are given almost nothing to do except collect a paycheck. Writer Grevioux is also an imposing actor with an impressive list of film and television badass roles. Here, as head security flunky to Naberius, he employs the vocal rhythms of George Takei, filtered through another couple layers of James Earl Jones-style basso profundo. He's the sole performer who seems as if he might be having any fun. To its minimal credit, I, Frankenstein never drags (too much of the action is a speeded-up blur), has some good visuals along with the bad (the electrical lab effects are quite nice, like James Whale and Fritz Lang on steroids) and will generally succeed in pleasing its intended, very undemanding audience. Since there's so little comprehensible plot to involve the viewer, details that ordinarily wouldn't command attention come to the fore. Could stone gargoyle wings really work? Talk about fallen angels. Adam tells us he's been stitched together from eight corpses, with a prominent scar bisecting his face. Was one of the corpses his twin? His features are handsomely symmetrical, like the rest of Eckhart's impressively ripped-and-stitched body. Will we ever see a Frankenstein monster that truly looks constructed of mismatched parts? Slain gargoyles, by the way, ascend to heaven on exactly (and I do mean exactly) the same shimmering columns of blue light by which Seth Rogen met his reward in last year's apocalyptic comedy This Is the End. We don't see what the goodly gargoyle afterlife looks like, but if Rogen got a celestial amusement park, we can assume that members of the Order of the Gargoyle rise at least to a bigger, better kind of game console in the sky. Dead demons, on the other hand, go where the goblins go, not so much below as up into coruscating CGI flames. Their sulfuric body composition apparently includes a fair ratio of Chinese gunpowder, specifically the kind that makes backyard bottle rockets go loop-the-loop. We see the effect over, and over, and over. These are some of the most uniquely inept computer-generated pyrotechnics you'll see this or any year, painfully flat animation akin to those Disney-created fireballs Cecil B. DeMille aimed at the stone tablets in The Ten Commandments. 3-D and Imax just make it worse. The costumes, while nicely designed and well-sewn, are conceptually anachronistic and sometimes just wrong. Christian warrior-gargoyles wear pre-Christian gladiator garb. The Gargoyle Queen looks faux-medieval, like she's stepped out of a Tarot card. In the 1780-something flashback, Eckhart's monster goes more than avant-garde (by centuries), sporting something like the trench-coat loner silhouette made viral by The Matrix in 1999. As with Stoker's Dracula, even the most misconceived and weirdly embellished adaptations of Frankenstein at least serve the commendable purpose of keeping the original story immortal. It's been suggested that the real reason Lionsgate walked away from its monster—for its U.S. release, at any rate—was not out of shame, but simply because domestic grosses have become irrelevant to a movie's ultimate success overseas. Millions of kids (and adults) all around the world spend billions of dollars on video games, and don't make much of a distinction between gaming and other forms of entertainment. A movie is just another thing that moves. In which case, the whole theme of Frankensteinish abandonment extends to the abject American film-going public itself, cast adrift upon a figurative ice raft on an indifferent sea of international commerce, and lost in the darkness and distance.

The artificial creation of life, or at least its convincing simulacrum, is also the theme of Spike Jonze's Her, in which a digital-age Everyman named Theodore Twombly (Joaquin Phoenix), who works for a high-tech company called beautiful-handwrittenletters.com, is having as much trouble making meaningful human connections as his clients. Cyrano-like, he ghost-writes their love letters and other heartfelt missives. The handwriting is computer-generated, of course, but it is pretty. And besides, isn't it the thought that counts? Los Angeles has become a deceptively sunny dystopia, its automobiles eliminated, its subway-to-the-sea finally realized, its skyline crowded with sleek-though-sterile office and apartment towers. Most of life's problems have been worked out, or at least smoothed out, but interpersonal relationships have suffered, with technology both the cause and cure. Enter Samantha, the Siri-like synthetic voice of Twombly's computer system (a superlative, deceptively understated voice performance by Scarlett Johansson). A model cyber-geisha, Samantha serves to please, and once she's pleasingly managing every aspect of the writer's life, they begin to date. And it's nothing to be self-conscious about; other people are doing it, too! I was afraid the story was heading squarely in the direction of a Big Reveal of a nefarious, Apple-like plot to control (or at least sexually humiliate) the world. There was also every possibility Her would easily careen in the farcical direction of Jonze's Being John Malkovich. Even as written, Jonze's script could well have been played for very cheap laughs (think Steve Martin, in The Man with Two Brains). Fortunately, Jonze takes a gentler, wistful route, aided immeasurably by Phoenix's haunted and vulnerable puppy-dog presence. And even though, deep down, we know this is a star-crossed romance, we hope against hope, rather in the way the world cheered for Boris Karloff in his naïve and fumbling expectation of happiness with the technologically engineered Elsa Lanchester. As this column goes to press, just before the 2014 Academy Awards ceremony, Her has been nominated for three Oscars—Best Picture, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Original Song—raising the perennial question: how on earth can a "best" film not also have the best acting and best direction? Maybe we should ask Samantha. | |

|

| ||

To contact us, send an email to Fantasy & Science Fiction.

Copyright © 1998–2020 Fantasy & Science Fiction All Rights Reserved Worldwide

If you find any errors, typos or anything else worth mentioning,

please send it to sitemaster@fandsf.com.